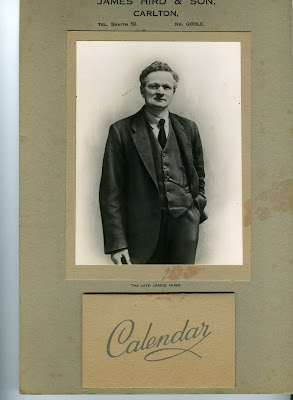

My great-grandfather, James Hird, started and ran a village shop in North Yorkshire. His trade background was with the Co-op, and he brought with him the Co-op ways of thinking, that worked for the well-being of customers and employees as well as shop-keepers. He was a thinking man with a vision for a fair and humane society. My great-grandmother, Nellie Hird (born Louisa Ellen Thornton; daughter of Mary Thornton, née Gott) worked alongside him in the establishment and running of the shop. She kept the accounts for the shop, and was also responsible for their household economy. At one point they were investigated by the Inland Revenue because the tax inspector didn’t see how they could run their home on so little money.

Before Nellie married she had worked in Bradford as a cloth designer. She and her sisters were artistic, capable, practical, intelligent, imaginative women. They made beautiful clothes and painted very good water-colours; they designed and stitched lovely tapestries. I remember Nellie’s garden, which was her pride and joy. For some years I kept a book she gave me when I was ten –

The Law of The Rhythmic Breath – a book about Hindu breathing exercises; which indicates something of the breadth of her mind and her high regard for the intellectual capacity of children. Even as a widow in her nineties, Nellie continued each week to cook herself a roast dinner (and then frugally eke out the meat in cold cuts and shepherds pies) and bake a Victoria sponge. She believed in home cooking, and she thought she was worth it. She died when I was thirteen, and I still have her commonplace book. I learned to write in copperplate handwriting, so I could follow on from the entries she had made – which in the main were poems and sayings exhorting and reminding of the value of a good attitude and positive spirit.

A vigorous, determined, kind, wise, fierce, tough, positive woman, I think it should be mentioned that an achievement of which Nellie was especially proud was staying supple enough into her nineties to lift her feet into the water of the washbasin.

Nellie and James had two children – Philip and Kitty (Kathleen). Kitty married Charles Turton, a very resourceful man. Charles was the son of a mother of harsh and zealous religion, and she instilled into him a certain hardness of attitude, which manifested in self-discipline and determination, but also in a certain personal coldness at times. Though he had this quality of aloofness and was not, I understand, the easiest man to live with, he was fair and generous – a good man. On the wall of his house he kept a framed motto:

Help thou thy brother’s boat across; and lo! thine own has touched the shore. And in the course of his life he did indeed through his own unremitting hard work raise the funds for his brothers to take their families to start a new life in Canada.

Charles was raised in a poor family; but he had aspirations. He started by renting a field in which he sowed peas. He left his father to tend the field, while he himself went to work on the cruise ships

Mauritania and

Aquitania as a silver-service waiter. Then he came back and harvested the peas, sold them, and with the proceeds rented two fields the following year, in which he sowed more peas. In not too many years, he had acquired a familiarity with the manners and requisites of fine dining in high society, earned a lot of money, bought a farm and a handful of other houses, and become probably the richest man in his village.

Kitty, my grandmother, worked alongside him in the farm office, keeping the books.

They had four children: Jeff, Mary, Jean and Jessie. Mary is my mother, and her memories of growing up on the farm (and summer holiday visits spent rambling happily about on that farm and the surrounding countryside) have shaped my concept of what life should be.

My mother was born in 1927, at a time when we are encouraged to imagine women were disenfranchised and excluded from the workplace: but the contribution of women in traditional society was very vivid in her experience.

Nellie’s background as a textile designer added flair to the practical skills and abilities that were taken for granted. Nellie and her sisters had hat blocks at home and were skilled milliners, for example. Once married, they didn’t go out to work for a wage so they could pay for a hat made by other women who worked for a wage in a hat factory – but why would they when they made their own? Nor did they go to the jewellers and pay for the services of a beautician to pierce their ears: they did it themselves at home with a needle and a cork, and a sock stuffed in their mouths to stop them screaming!

When anyone in the family had a baby, Aunt Jessie – one of Nellie’s unmarried sisters – would move in for a while to take over the household tasks. Aunt Pat was a teacher. My mother remembers going to stay with Aunt Kate and Uncle Hubert – an exotic household where wide-eyed little Mary marvelled that they sometimes ate cake for breakfast! One of Uncle Hubert’s habits was of keeping a sharp eye out when he went out for a walk, for dropped handkerchiefs. He’d bring them home for Aunt Kate. Hearing this as I child, I thought it a wonderful idea – and from childhood still to this day I do the same (except I have to be Aunt Kate as well as Uncle Hubert in this enterprise).

The farm where Mary (my mother) grew up was alive with people. Every year my grandfather would go to the labour market to choose his work-force for the coming year, and during the war his farm labourers included prisoners of war. My mother was curious to meet them – wondered what they would be like, these Germans! It was a formative insight when she, a child looking on, realised that the enemy was –

just like us!

On the farms in those days, the women managed the dairy and the poultry, and the garden, while the menfolk took care of the fields of grain and beet and beans.

While Kitty was busy running the farm office, the household was run by Suzy, a woman from the village, who became in effect a member of the family. She raised the children, and did all the housework, and my mother loved her dearly. Time spent in Yorkshire in my childhood always included a visit to Suzy and George’s small redbrick cottage: I loved the simple living room, with its low ceiling and huge kitchen range; the couch drawn up before the fire, a home-made rag rug before the hearth, everything homely and welcoming.

Those were the days before ensuite bathrooms – or even indoor toilets. The family were the proud owners of a very upmarket privy; a two-seater, no less! But Yorkshire is cold, and the privy was for the movement of the bowels only. For passing urine, everyone had chamber-pots: and emptying the chamberpots from the bedside nightstands each morning was Suzy’s job. Suzy cleaned all the windows every week. Suzy scrubbed the floors and cooked the pies. And she was beloved. And she was dignified: in that culture, manual work was not demeaning.

My mother grew up wandering happily around the farm. Self-reliant and independent; as a little tot, if she wet her knickers she took them off and buried them; earning the affectionate epithet ‘Dirty Blossom’ from Aunt Jessie when she came to help in the house.

Himsworth Farm, where my mother grew up, was a mixed farm. I remember from my own childhood the bullocks standing patiently at the field gate beside the barn, their breath in clouds of steam on the frosty air. Big vats of potatoes were boiled up for the pigs, and my mother as a child used to sit on the stone steps of one of the brick farm buildings, eating pig potatoes with a sprinkle of salt and a dab of butter – and ‘pig potatoes’, boiled in their skins and seasoned with salt and butter, became one of the delights of my own childhood.

My mother learned from her mother and grandmother about household economy – how to make the budget stretch to miracles. She learned from her father, who had inched his way up from a rented field of peas to his own farm, how precious is the land, and how dearly prized the chance to ‘own’ a piece of it. She saw how men and women worked together as a team to create stability and prosperity: a marriage that was a firm as well as a personal relationship. That team was the core of prosperity, and generated trade relationships; and work, shelter and belonging for a whole tribe of relatives, employees. It gave people a place in the world, meaningful work and productive lives. It made people capable and resourceful, and gave them a sense of purpose.

Once, as a girl, my mother grumbled about all the work to be done – and my grandmother turned to her in some amazement saying, ‘But what would we do, without work?’

Work meant contentment, to those people.

My mother applied what she had learned in childhood in her own life. She knew the ways of frugality and economy: she sometimes spoke to me of two farm labourers that stayed in her memory; they both had the same wages, but one always had meat or cheese with the bread of his packed lunch, while the other had to be content with ‘pepper-and-salt-sandwiches’ – the difference was in the way the woman at home was managing the household budget.

In my own childhood, I remember gardens that could have won a prize – my mother grew flowers like the fields of heaven. I remember as a toddler, standing among dahlias as tall as myself, seeing the diamonds of dew held in their gaudy petals, smelling their sharp, clean scent. I remember learning the names of flowers as soon as I learned to talk; going along the herbaceous beds at my mother’s side, emphasising every syllable with a jabbing finger, exclaiming ‘these are the me-sem-bry-an-the-mums!’

My mother never took a job outside the home: home was where she wanted to be. My father’s income was small, and his work took him travelling all over the world, so he was often absent: but with the help of a modest amount of inherited money and years of the tightest budgeting imaginable, she eventually achieved a redbrick sprawling house in five acres of land, with an orchard, a wood, a walled vegetable garden and paddock, and a river running through it. There we raised sheep and kept hens, grew fruit and vegetables and flowers. For me as a teenager, eating an apple meant wandering through the orchard from tree to tree, choosing which one to pick, and eating it with the rain still on it. Coming in from school ravenously hungry, ready for a sandwich, I would stop by the greenhouse and pick a ripe tomato warm from the sun, and that sprinkled with a smidgin of salt went in the new bread from the village bakery to put me on until supper time. And when supper time came, I would be sent out to cut some asparagus, or pick some French beans, to go with an omelette from our hens, or some of our grass-fed lamb.

My mother was one of those who ‘never went out to work’! Yet on a summer evening, oftentimes she would be sitting up until two or three in the morning, her fingers stained with the ingrained juice of vegetables, podding and blanching broad beans for the freezer, peeling and coring and stewing apples, ready for the long days of the winter.

I am so grateful for the wisdom and influence of traditional women, strong women, in my life. They held their families together; quiet and gentle in their exterior, and as tough as baked leather underneath.