Two of my mother's favourite perspectives:

"Don't draw attention to yourself."

"Don't rock the boat."

She believed (still does) in slipping through the world, as Ezra Pound put it, "like a field mouse, not shaking the grass", in the Taoist ideology of find your way like water round the immovable stones in life's river bed.

She rarely engaged in conflict, or responded to provocation, preferring to just raise her eyebrows and go her own way. She dealt with the difficulties of interaction with the human race by not entering it. She has been the archetypal cat that walks alone. She kept her own counsel, went her own way.

Yet for all that, here and there when she saw it as necessary, she stood her ground.

When I was about fifteen I watched an encounter she had with a man who came to fell a dangerous dead branch from an oak tree on our land, overhanging the road. He charged an eye-watering sum and we were chronically poor. My mother said nothing when she received his request for payment, just got out her cheque book. He (a somewhat oily type) said to her, in receipt of her cheque, "If ever you're in trouble again, just get in touch."

And she replied, "If I'm ever in trouble, I'll get out of it somehow without coming to you."

She could hold her own, when she saw fit to do so. I logged the conversation in the Useful Items section of my memory.

When I was a little girl, about seven, she gave me a little book that I loved, called A Pocketful of Proverbs.

I knew most of the proverbs in the book already — which is itself always a delight to a child — but there was one new to me:

Of all the sayings in the world

The one to see you through

Is never trouble trouble

Until trouble troubles you.

It caught my attention, amused me because of the word play, and gave me a great deal of food for thought. One of the questions quick to my mind is, "Is that true?" I asked it of myself about the proverb. On balance, I thought it was true. Letting sleeping dragons lie is, in general, a wise rule of thumb.

But one should not be deluded that it comes without cost.

Excuse me if (yawn) you are well familiar with this word, but have you much thought about casuistry?

The definitions of it online are almost as complex and abstruse as the concept itself.

It first caught my attention when I came across it as a young woman, in someone's (I forget whose) reference to the casuistry of the Roman Catholic Church — the overlooking of the actual application of the draconian rules (eg about contraception and celibacy) that people found impossible to keep. The priest and his 'housekeeper', for example. People finding their way like water round the blocks. People who had decided that of all the sayings in the world the one to see them through was never trouble trouble until trouble troubles you.

Casuistry occurs when pragmatism meets ideology.

I have come across it happening right now in the Methodist Church, where our Safeguarding programme has escalated almost to the level of an obsession. In Circuits where Local Preacher ongoing training has simply run into the mud and stopped, Safeguarding training is proliferating like mushrooms on dead wood.

I am all for safeguarding children and vulnerable adults from harm, and I think the best way to do it is to respect and listen to them, to include them in decision-making, and to give them the space and opportunity to be heard and to stand up for themselves. What we do instead is infantilise those who are not in power, imposing on them decisions made behind closed doors by Those Who Know Better, and imposing on them, wholesale, edicts from above.

And this is where the casuistry arises. So dense and unrealistic is the programme we have rolled out that its application is impractical. Let me give you an example.

At our recent training, we were offered the case study of a church that wanted to set up a 'Wednesday Club' serving lunches for old people, including some with dementia. We were given a list of those who would be required to run it, and asked what action would be needed (police checks, interviews, clear rôle descriptions and boundaries, and work partners) for the manager, assistant manager, minibus driver, kitchen volunteers and volunteers to chat with and serve lunch to the people for whom the club would run.

Actually, thinking of the nature and membership of our Circuit's Methodist church congregations, the answer to all of it was short and simple: no Wednesday Club, then — make your own lunch.

But the church is peopled by irenic souls who believe that of all the sayings in the world, the one to see you through, is never trouble trouble until trouble troubles you. They flow round the impracticalities like water round stones — gently acquiescing to the draconian legislation imposed upon them, but (crucially) only very selectively applying it; thus rendering it, of course, ineffective.

A couple of decades ago I had a run-in with Methodism over this very issue. A then senior official in that denomination, having been made to apologise by a better man than himself for all the insults and lies he had flung at me, subsided rumbling, saying that I was born to rattle the cage of the Methodist Church.

And as long as the church deals in cages, may it be so.

The big problem with the church's Safeguarding programme, is that the same people who made it necessary are running it. If it is administered with kindness, intelligence and humanity, it will make the world a safer and gentler place. But that's not the outcome of the programme, it's the outcome of kindness, intelligence and humanity. If it's run by bullies or the inept, it merely serves to magnify the scope of their influence. I've seen it ignored when it suited church leaders, and I've seen it applied to crush and exclude people when that in turn suited church leaders. The bottom line is, you cannot legislate for goodness, or institutionalise it. You can only live it.

My mother has, time and again, said to me "Don't draw attention to yourself," and, "Are you rocking the boat again, Penelope?"

Like anyone, I prefer a quiet life. But when it comes to that proverb about never troubling trouble, for me the jury's still out. I will never go looking for trouble, but when it comes to safeguarding any human being including myself, I think I prefer the approach of this song by Elvis Presley, which is also logged in the Useful Items compartment of my memory.

Though I hope in my own case, I am neither miserable nor evil; merely determined to see truth emerge.

Thursday, 29 November 2018

Made me laugh today

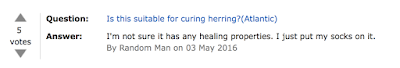

You know how, on Amazon, customers can send in a question which is then emailed out to other customers who've bought the product?

Today, looking at socks airers on Amazon — specifically, this one:

Today, looking at socks airers on Amazon — specifically, this one:

. . . I came across this question and answer (click on it if it's too small for you to read properly):

Tuesday, 27 November 2018

Day off, is it?

"You have won the game. Time, 8.43."

Fine. Twelfth game of Spider Solitaire. Now what?

We have builders.

Working from home is a hard-won prize to be jealously guarded, the fruit of decades of strategic life choices, grown in the compost of determined simplicity: small budget, low income, few possessions, sparse schedule, and no social circle whatsoever — just a sketchy outline of friendship almost too faint to make out.

But, though working from home is a privilege to which I tightly cling, it does have its drawbacks. And one of them is that, from the perspective of those who are not yourself but everyone else, you are clearly completely unoccupied. You are the obvious sentinel, gofer (I had to check how to spell that; a gopher is something else) and companion of those who are at a loose end.

When the household schedules building works, its members then leave the premises, all except for Guess Who.

It is a blessing that these days builders have no wish to speak to me. Well — only if they need to. Like yesterday morning — BANG BANG BANG on my door.

"Yes? Can I help?"

"Can you come and look at this. You got lead."

"Ah yes. So I see."

"Only, we don't do lead. It's split. Musta been like that for years. And we don't do lead. We don't carry lead."

"Oh, dear. What should we do?"

"Well, if you get the lead, we can put it in, but, see, we don't do lead. We don't carry lead."

You get the drift? You have absorbed the point? They don't do lead.

Happily, yesterday, my best beloved had also fallen into the trap of working from home, and was willing to go up to Travis Perkins building supplies merchant for 6 metres of lead. Though what the hell we shall do with the surplus two metres I have no idea. Freegle it, I guess.

Other than when such emergencies arise, though, I am grateful to be entirely see-through to builders nowadays. I have hair like mouldy hay, a midriff like a Sherman tank and features like Les Dawson.

In parenthesis, in case you have never heard of Les Dawson, a northern-English comedian:

But years ago when I was young and lithe with long blonde hair, and even then worked from home, they were more inclined to chat.

The opening gambit never varied:

"Day off, is it?"

I have always been more than a little Aspergery, but even I know the correct response to such an enquiry is not (however mellow one's tone):

"No, you moron. I am here because you are."

At the age I am now, I would just say, "Yes."

I mean — why go to the bother?

But as a young woman, chronically worried about seeming lazy or under-productive or insufficiently hard-working or in any way unsatisfactory, I would start to explain that, well, no, I work from home, I am a writer, I . . . No one is ever listening. Or was even then.

It's so much easier now. I am clearly just the old biddy who keeps house for the Ones Who Have Jobs, and are therefore elsewhere. Because the whole working world is elsewhere, right?

Last Sunday, a complete stranger made the error of getting into conversation with me while I stood by our car with the door open. The other half of me-and-him was getting eggs from the garden gate next to our chapel (rescue hens and eggs at £2 a dozen, where the supermarket ones are £2.15 for six). So this lady plus small dog paused to chat on her way home with her own eggs. We talked (as you do) about her dog — how sweet, how pretty, etc. I do have a few social skills, and it was, in all fairness, a nice dog.

She told me how the dog had come into her life. What had happened was that her son Gary had woken up in the night a few months ago, asking himself why his wife Ruth didn't work. I'm not sure in what sense she didn't work. Like a defunct washing machine perhaps, or a clogged vacuum cleaner. Who knows? But evidently Gary felt dissatisfied with this arrangement. He pointed out to Ruth that she hadn't worked ("at all", as his mother put it) for twelve years and now it was time she did. Ruth conceded that their three children could be left to fend for themselves and their house remain uncleaned. They could eat freezer food and take-away pizzas (I am making this up, the dog lady left out that part), but who would look after the dog? A dog needs a companion. So Gary said they'd give the dog to his mother: and so they did.

I listened to this.

"Gary should be careful," I eventually replied. "He might find, once Ruth is financially independent, she may discover she doesn't need Gary at all."

Swifter than an ostrich on speed, "Oh, no!" responded the dog lady: "No, no, no! No. Gary's very good."

At what, I wondered, but thought it might seem indelicate to enquire.

But Ruth was quite right. The spiritual power of dogs is that they help us to understand the virtue of companionship.

And in the evening of the day I met Dog Woman, I went to a concert (our Rosie was playing trombone) where a friend wanted to tell me how lonely she was. What she hated, in particular, was coming home to an empty house. Let's hope Gary doesn't mind, eh? And let's hope he has a liking for Indian takeaways, because I don't think anywhere delivers roast dinners at eight o'clock in the evening. And I wonder what he'll do if they need to have builders in?

But maybe I sound sour and should shut up now. Or someone's eye may fall on the spine of To Kill A Mocking Bird and mistake it for a word from the Lord.

I want to write about the Four Accessibilities and also about Politics, Nutrition, Money and Religion — but that will have to wait until Thursday when these drills and sanders and rivet guns (and that whatever it is that shakes the house like a volcano and an avalanche competing for top spot) have gone their merry way.

Uh-oh. Heavy boots in the passage. Bye now.

Then I'm going to play a thirteenth game of solitaire and have a cup of tea.

And what about you? Why are you here, reading this? Day off, is it?

Fine. Twelfth game of Spider Solitaire. Now what?

We have builders.

Working from home is a hard-won prize to be jealously guarded, the fruit of decades of strategic life choices, grown in the compost of determined simplicity: small budget, low income, few possessions, sparse schedule, and no social circle whatsoever — just a sketchy outline of friendship almost too faint to make out.

But, though working from home is a privilege to which I tightly cling, it does have its drawbacks. And one of them is that, from the perspective of those who are not yourself but everyone else, you are clearly completely unoccupied. You are the obvious sentinel, gofer (I had to check how to spell that; a gopher is something else) and companion of those who are at a loose end.

When the household schedules building works, its members then leave the premises, all except for Guess Who.

It is a blessing that these days builders have no wish to speak to me. Well — only if they need to. Like yesterday morning — BANG BANG BANG on my door.

"Yes? Can I help?"

"Can you come and look at this. You got lead."

"Ah yes. So I see."

"Only, we don't do lead. It's split. Musta been like that for years. And we don't do lead. We don't carry lead."

"Oh, dear. What should we do?"

"Well, if you get the lead, we can put it in, but, see, we don't do lead. We don't carry lead."

You get the drift? You have absorbed the point? They don't do lead.

Happily, yesterday, my best beloved had also fallen into the trap of working from home, and was willing to go up to Travis Perkins building supplies merchant for 6 metres of lead. Though what the hell we shall do with the surplus two metres I have no idea. Freegle it, I guess.

Other than when such emergencies arise, though, I am grateful to be entirely see-through to builders nowadays. I have hair like mouldy hay, a midriff like a Sherman tank and features like Les Dawson.

In parenthesis, in case you have never heard of Les Dawson, a northern-English comedian:

But years ago when I was young and lithe with long blonde hair, and even then worked from home, they were more inclined to chat.

The opening gambit never varied:

"Day off, is it?"

I have always been more than a little Aspergery, but even I know the correct response to such an enquiry is not (however mellow one's tone):

"No, you moron. I am here because you are."

At the age I am now, I would just say, "Yes."

I mean — why go to the bother?

But as a young woman, chronically worried about seeming lazy or under-productive or insufficiently hard-working or in any way unsatisfactory, I would start to explain that, well, no, I work from home, I am a writer, I . . . No one is ever listening. Or was even then.

It's so much easier now. I am clearly just the old biddy who keeps house for the Ones Who Have Jobs, and are therefore elsewhere. Because the whole working world is elsewhere, right?

Last Sunday, a complete stranger made the error of getting into conversation with me while I stood by our car with the door open. The other half of me-and-him was getting eggs from the garden gate next to our chapel (rescue hens and eggs at £2 a dozen, where the supermarket ones are £2.15 for six). So this lady plus small dog paused to chat on her way home with her own eggs. We talked (as you do) about her dog — how sweet, how pretty, etc. I do have a few social skills, and it was, in all fairness, a nice dog.

She told me how the dog had come into her life. What had happened was that her son Gary had woken up in the night a few months ago, asking himself why his wife Ruth didn't work. I'm not sure in what sense she didn't work. Like a defunct washing machine perhaps, or a clogged vacuum cleaner. Who knows? But evidently Gary felt dissatisfied with this arrangement. He pointed out to Ruth that she hadn't worked ("at all", as his mother put it) for twelve years and now it was time she did. Ruth conceded that their three children could be left to fend for themselves and their house remain uncleaned. They could eat freezer food and take-away pizzas (I am making this up, the dog lady left out that part), but who would look after the dog? A dog needs a companion. So Gary said they'd give the dog to his mother: and so they did.

I listened to this.

"Gary should be careful," I eventually replied. "He might find, once Ruth is financially independent, she may discover she doesn't need Gary at all."

Swifter than an ostrich on speed, "Oh, no!" responded the dog lady: "No, no, no! No. Gary's very good."

At what, I wondered, but thought it might seem indelicate to enquire.

But Ruth was quite right. The spiritual power of dogs is that they help us to understand the virtue of companionship.

And in the evening of the day I met Dog Woman, I went to a concert (our Rosie was playing trombone) where a friend wanted to tell me how lonely she was. What she hated, in particular, was coming home to an empty house. Let's hope Gary doesn't mind, eh? And let's hope he has a liking for Indian takeaways, because I don't think anywhere delivers roast dinners at eight o'clock in the evening. And I wonder what he'll do if they need to have builders in?

But maybe I sound sour and should shut up now. Or someone's eye may fall on the spine of To Kill A Mocking Bird and mistake it for a word from the Lord.

I want to write about the Four Accessibilities and also about Politics, Nutrition, Money and Religion — but that will have to wait until Thursday when these drills and sanders and rivet guns (and that whatever it is that shakes the house like a volcano and an avalanche competing for top spot) have gone their merry way.

Uh-oh. Heavy boots in the passage. Bye now.

Then I'm going to play a thirteenth game of solitaire and have a cup of tea.

And what about you? Why are you here, reading this? Day off, is it?

Living light

I used to find living through winter darkness very hard.

When I looked into it more deeply, though, I wondered if I might be starved of living light rather than merely of sunlight. So I adjusted what I was doing, and found my suspicions well-founded.

I love sunny days. But . . .

. . . if I have firelight

When I looked into it more deeply, though, I wondered if I might be starved of living light rather than merely of sunlight. So I adjusted what I was doing, and found my suspicions well-founded.

I love sunny days. But . . .

. . . if I have firelight

and starlight (in good company with Jesus who is the living light)

and moonlight

and dawn light

and the slanting light of the afternoon

and candle-light

then I find my soul is fed with the wonder and mystery it needs to stay steadily strong.

And it is a mistake to think of a fire

as merely a heat source.

If you have a fire in your home, you have a pet dragon.

A fire eats and breathes, it speaks, it is full of personality and different every day. A fire is a friendly companion, with the added spice of being distinctly and uncompromisingly dangerous; the sort of friend who can destroy your living room in under two minutes and think it's funny.

Having a fire on your hearth is akin to inviting the sea to live with you, or swapping out your roof for the starry sky like Jesus did. Elemental.

I respect the experience and testimony of those who experience SAD. Without doubt it is a thing.

But

I humbly offer the view that it is a thing one might deepen and worsen by going into the winter with central heating and closed curtains.

Living light makes life better.

All living light. And firelight, after all, is the sunshine stored in the remembering heart of a tree. I am thankful for the trees who gave their lives that I might be comforted all through the cold dark months of winter by living light. What a treasure. What a precious and wonderful gift.

Saturday, 24 November 2018

Non-compliance

I am really looking forward to worship tomorrow, at our little chapel at Pett. I personally have absolutely no preaching or leading duties tomorrow, so get the chance to enjoy some else's input.

And tomorrow morning — that's November 25th at 10.45am — our preacher is Buzzfloyd who often comments here. In the Methodist Church, when we talk about a preacher we don't just mean the person who gives the address. The preacher is responsible for crafting the entire act of worship.

I am specially looking forward to tomorrow's worship for four reasons.

Firstly, Buzzfloyd is a cracking good preacher — engaging, unfailingly interesting and thought-provoking, kind and full of faith.

Secondly, I know she has recently been thinking about non-compliance as a social skill — as an asset rather than a problem — and I am hoping she may be sharing some of her thoughts about that tomorrow.

Thirdly, it is all-age worship, which suits our congregation at Pett very well. We are genuinely all-age, ranging from toddlers to grannies, and everyone is full of good ideas and they all offer brilliant insights and contributions when given the chance. And I know that Buzzfloyd can be trusted to ask honest questions in search of real answers — as opposed to the tired ruse of asking leading questions to oblige the people to second-guess the answer the preacher prepared earlier.

Fourthly, Buzzfloyd has a substantial praise section lined up for us, and as the word of God goes forth upon the praises of the people, we know that this is just the best way to enable the flow of the Spirit in our midst; which after all is why we go to church.

So it's going to be brilliant and good fun and interesting and I've been looking forward to it all week, and if you live in East Sussex your journey to join us would not be wasted. If you live in the US you may be just in time to catch a flight but if you're in Australia you might be cutting it a bit fine even if you start out now.

Fabric and weather

I live on the south coast of England, where the weather is much warmer and gentler than in the north. Even so, we have the three of four seasons requirements of our clothing.

Typically, January is deeply cold and frosty; if it snows, it's most often in January.

February is a very cold month, and usually has light persistent rain most of the time. It's the time when the light returns, a good spring-cleaning month as the lemon-juice sunshine illuminates all the cobwebs! The snowdrops (Fair Maids of February) are in bloom. The ramsons are up.

March is a blustery month — very cold, sharp, north-easterly winds — and often bright, clear, joyous sunshine. The daffodils are up and blooming.

April is the month when as a young woman I determinedly wore my new summer dresses and felt absolutely freezing cold. Definitely springtime, but definitely still very cold. Still the month for daffodils and tulips, and the fruit trees also coming into blossom — cherries first. Late frosts sometimes catch the blossom before it sets.

Then May brings the greening of England — all the trees coming fully into leaf, and the woods glorious with bluebells. The lilies of the valley come into bloom.

June is high summer, the zenith of the light at St John's tide over the summer solstice. The trees come into full canopy, and all the plants like green alkanet and Queen Anne's Lace and comfrey and ragged robin and Traveller's Joy and feverfew and heal-all and eyebright and everything are in bloom. It can still be a cool month, but also blazing hot. It can be rainy — or not. I've even known it snow in June!

July is usually a hot month. The soft fruit like strawberry, cherries and raspberries continue, that began to appear in June. The beans and courgettes and tomatoes start to be ready.

In August the summer begins to turn, the grass often going brown in the heat, the trees still in full canopy but a different sniff to the wind. It can be a turbulent month, with electrical storms and a surprising amount of rain.

September is a golden month — time for the grain harvests. Of all the days in any given year, the one most likely to be fine and warm and dry is September fourteenth. It's a lovely month — long, warm evenings, very mellow. The nights freshen with lower temperatures towards the end of the month, bringing the gold and red colours to the leaves of all the deciduous trees.

October is blustery and wild, with wind and rain storms; very invigorating and refreshing, time to get out coats and sweaters as the last leaves are blown from the trees.

November is often drizzly and misty, the frosts begin and the nights draw in. It can be still surprisingly warm right into mid-November, but at that point the subtle change from autumn to winter takes effect.

December is often warmer than either November or January, often quite a dry month with less wind. Sharp frosts at night and clear, starry skies very often — great for carol-singing! The winter solstice (Yul) comes just before Christmas, and after that the light returns by twenty minutes every week.

So our weather is quite variable!

Micro-fleece, while being bad news for the oceans by shedding tiny plastic fibres into the water-courses that eventually get absorbed into our bodies via the food chain, is very handy for the many English days characterised by light drizzle and chilly wind (autumn, spring). Indian cotton and linen are perfect for the high summer. But now, as we go into the coldest part of the year, layered wool is the very best thing. If you layer cotton, the result is often heavy and restrictive of movement. If you layer micro fleece your skin can't breathe and it feels suffocating. But layered wool is cosy without being too hot.

Today, I have a long-sleeved cotton t-shirt, and over that a medium weight cashmere cardigan buttoned up to wear like a sweater, and over that a longer, heavier cashmere cardigan worn open. And even in my north-facing room with no heating, my nose is cold but I am comfortably warm. I have snuggly micro-fleece trousers and very cosy slippers.

Typically, January is deeply cold and frosty; if it snows, it's most often in January.

February is a very cold month, and usually has light persistent rain most of the time. It's the time when the light returns, a good spring-cleaning month as the lemon-juice sunshine illuminates all the cobwebs! The snowdrops (Fair Maids of February) are in bloom. The ramsons are up.

March is a blustery month — very cold, sharp, north-easterly winds — and often bright, clear, joyous sunshine. The daffodils are up and blooming.

April is the month when as a young woman I determinedly wore my new summer dresses and felt absolutely freezing cold. Definitely springtime, but definitely still very cold. Still the month for daffodils and tulips, and the fruit trees also coming into blossom — cherries first. Late frosts sometimes catch the blossom before it sets.

Then May brings the greening of England — all the trees coming fully into leaf, and the woods glorious with bluebells. The lilies of the valley come into bloom.

June is high summer, the zenith of the light at St John's tide over the summer solstice. The trees come into full canopy, and all the plants like green alkanet and Queen Anne's Lace and comfrey and ragged robin and Traveller's Joy and feverfew and heal-all and eyebright and everything are in bloom. It can still be a cool month, but also blazing hot. It can be rainy — or not. I've even known it snow in June!

July is usually a hot month. The soft fruit like strawberry, cherries and raspberries continue, that began to appear in June. The beans and courgettes and tomatoes start to be ready.

In August the summer begins to turn, the grass often going brown in the heat, the trees still in full canopy but a different sniff to the wind. It can be a turbulent month, with electrical storms and a surprising amount of rain.

September is a golden month — time for the grain harvests. Of all the days in any given year, the one most likely to be fine and warm and dry is September fourteenth. It's a lovely month — long, warm evenings, very mellow. The nights freshen with lower temperatures towards the end of the month, bringing the gold and red colours to the leaves of all the deciduous trees.

October is blustery and wild, with wind and rain storms; very invigorating and refreshing, time to get out coats and sweaters as the last leaves are blown from the trees.

November is often drizzly and misty, the frosts begin and the nights draw in. It can be still surprisingly warm right into mid-November, but at that point the subtle change from autumn to winter takes effect.

December is often warmer than either November or January, often quite a dry month with less wind. Sharp frosts at night and clear, starry skies very often — great for carol-singing! The winter solstice (Yul) comes just before Christmas, and after that the light returns by twenty minutes every week.

So our weather is quite variable!

Micro-fleece, while being bad news for the oceans by shedding tiny plastic fibres into the water-courses that eventually get absorbed into our bodies via the food chain, is very handy for the many English days characterised by light drizzle and chilly wind (autumn, spring). Indian cotton and linen are perfect for the high summer. But now, as we go into the coldest part of the year, layered wool is the very best thing. If you layer cotton, the result is often heavy and restrictive of movement. If you layer micro fleece your skin can't breathe and it feels suffocating. But layered wool is cosy without being too hot.

Today, I have a long-sleeved cotton t-shirt, and over that a medium weight cashmere cardigan buttoned up to wear like a sweater, and over that a longer, heavier cashmere cardigan worn open. And even in my north-facing room with no heating, my nose is cold but I am comfortably warm. I have snuggly micro-fleece trousers and very cosy slippers.

Friday, 23 November 2018

Jephthah's bandits and the anarchist church

Nearly twenty years ago I instigated a Fresh Expression Of Church called the Universal Glue Factory — a name inspired by Wayne Dyer's speaking of love as the glue that holds the universe together.

We did a variety of things, and meeting for worship was obviously one. Our worship meeting we called Jephthah's Bandits — because we had found ourselves outside the church by an improbable coincidence of circumstances.

But the name Jephthah may not immediately be familiar to you. In case not, let me tell you about him.

Jephthah's tragic story is told in the book of Judges (chapter 11). He was a mighty warrior, the offspring of Gilead and a prostitute. Gilead had other sons born within the institution of marriage, who, when they reached adulthood, drove Jephthah out of the family. They didn't want to share their inheritance with him, and felt that he had no right to it because he was not properly part of the family, since his mother was not Gilead's wife. The offspring of establishment is security; but also sometimes is lack of imagination, casual cruelty and segregation.

So, dispossessed and alone, he made common cause with a group of bandits — men in a similar situation — who, like Peter Pan's lost boys, all hung out together.

Later on, when Israel went to war against the Ammonites, Jephthah's brothers came to look for him — they now needed his skill in battle. Craving their acceptance, he returned to fight for them. Desperate to seal his inclusion, he bargained with God. He promised to offer in sacrifice the first creature that should meet him on his return from war. He came back victorious, and on the way home was met by his daughter, dancing and singing in celebration of his victory. Like all people caught up in cycles of abuse and rejection, his first instinct was to blame her for the fate that now awaited her — look what misery you've brought on my head! She asked for a little time together with her friends, which he granted her, and then he put her to death. We do not know her name. The story contrasts strikingly with the binding of Isaac, in which God provides a ram to avert the sacrifice of Abraham's son.

The offspring of exclusion and rejection is an ongoing destructive cycle, the tragedy of wasted life, nameless, unrecognised, unrecorded.

So that's Jephthah.

Why I think of him in connection with the anarchist church is because I see him, and his bandits in their hideout in the hills, in the modern world.

I see the "dones" — those who have tried their best with church and, disappointed and disillusioned, are done with it. I see those who fall foul of the structures, requirements and regulations of the church, and wander dispossessed, those whose ministry and gifts are rejected or neglected, who are not pastored in times of grief, who are left like sheep wandering on the fells without a shepherd. It is not so much the community that does this, for they have surrendered their power to the institution. They watch from the sidelines, unsettled but silent, as things take their course. Jephthah's daughter is delivered nameless and alone to her death, because for her there is no angel to intervene.

When an asteroid hits a planet and blows it apart, the debris is scattered locally in space, but begins to whirl in its familiar patterns of orbit, reassembling in a mish-mash of components as it is drawn together again. It sorts itself out in time. This also happens to people.

An anarchist church would allow people to find their own level, tell their own story, put their lives back together and begin to heal. The pain of rejection, the patterns of inclusion and exclusion, would no longer apply, because there would be no hierarchical pyramid, no power structure; only a circle in which, under the eyes of everybody, anybody could take their place.

In the end, I think, the scattered debris of Jephthah's bandits will form into an anarchist church. It will only be a matter of time.

We did a variety of things, and meeting for worship was obviously one. Our worship meeting we called Jephthah's Bandits — because we had found ourselves outside the church by an improbable coincidence of circumstances.

But the name Jephthah may not immediately be familiar to you. In case not, let me tell you about him.

Jephthah's tragic story is told in the book of Judges (chapter 11). He was a mighty warrior, the offspring of Gilead and a prostitute. Gilead had other sons born within the institution of marriage, who, when they reached adulthood, drove Jephthah out of the family. They didn't want to share their inheritance with him, and felt that he had no right to it because he was not properly part of the family, since his mother was not Gilead's wife. The offspring of establishment is security; but also sometimes is lack of imagination, casual cruelty and segregation.

So, dispossessed and alone, he made common cause with a group of bandits — men in a similar situation — who, like Peter Pan's lost boys, all hung out together.

Later on, when Israel went to war against the Ammonites, Jephthah's brothers came to look for him — they now needed his skill in battle. Craving their acceptance, he returned to fight for them. Desperate to seal his inclusion, he bargained with God. He promised to offer in sacrifice the first creature that should meet him on his return from war. He came back victorious, and on the way home was met by his daughter, dancing and singing in celebration of his victory. Like all people caught up in cycles of abuse and rejection, his first instinct was to blame her for the fate that now awaited her — look what misery you've brought on my head! She asked for a little time together with her friends, which he granted her, and then he put her to death. We do not know her name. The story contrasts strikingly with the binding of Isaac, in which God provides a ram to avert the sacrifice of Abraham's son.

The offspring of exclusion and rejection is an ongoing destructive cycle, the tragedy of wasted life, nameless, unrecognised, unrecorded.

So that's Jephthah.

Why I think of him in connection with the anarchist church is because I see him, and his bandits in their hideout in the hills, in the modern world.

I see the "dones" — those who have tried their best with church and, disappointed and disillusioned, are done with it. I see those who fall foul of the structures, requirements and regulations of the church, and wander dispossessed, those whose ministry and gifts are rejected or neglected, who are not pastored in times of grief, who are left like sheep wandering on the fells without a shepherd. It is not so much the community that does this, for they have surrendered their power to the institution. They watch from the sidelines, unsettled but silent, as things take their course. Jephthah's daughter is delivered nameless and alone to her death, because for her there is no angel to intervene.

When an asteroid hits a planet and blows it apart, the debris is scattered locally in space, but begins to whirl in its familiar patterns of orbit, reassembling in a mish-mash of components as it is drawn together again. It sorts itself out in time. This also happens to people.

An anarchist church would allow people to find their own level, tell their own story, put their lives back together and begin to heal. The pain of rejection, the patterns of inclusion and exclusion, would no longer apply, because there would be no hierarchical pyramid, no power structure; only a circle in which, under the eyes of everybody, anybody could take their place.

In the end, I think, the scattered debris of Jephthah's bandits will form into an anarchist church. It will only be a matter of time.

Thursday, 22 November 2018

Life in a teeny-tiny Tokyo Apartment

This woman has the neatest bathroom ever!

Structuring meetings in an anarchist church

So yesterday at home we were talking about the practical organisation of meetings in an anarchist church. If it's all a circle and belongs to everyone, how would anything actually get done?

This is what I imagine.

In any given act of worship, I envisage the inclusion of the following elements:

This is what I imagine.

In any given act of worship, I envisage the inclusion of the following elements:

- Prayer — adorational, intercessory, petitionary and prayer of thanksgiving and response.

- Ministry of the Word — reading and exposition of the Scriptures, and teaching of the faith.

- Music — hymns and songs, sometimes instrumental music to listen to, maybe music and dance.

- Ministry — the exercise of gifts of the Spirit in healing, words of knowledge and wisdom, prophecy, tongues and interpretation.

- Participation — discussion, open prayer, creative activity of various kinds (eg making things, action songs, dance, performed music, enacted prayers and dramatisation of scripture)

How I imagine an anarchist church coming about is a seed initiative by a small motivated group of mature Christians, gradually establishing and accumulating further members who integrate with and add to the existing group so that the whole enlarges organically (rather than being manufactured/planted/set up).

I imagine such a congregation would begin with, say, half a dozen like-minded souls through whom a pattern of worship and organisation would emerge by exploration, discussion, experimentation, listening and prayer.

Perhaps it would then grow to a group of about twenty or thirty members. At that point, it would become unwieldy for everyone to discuss everything. So then the organisation of worship could be done through a rota of sub-groups. All the people would be allocated to a group — if there were twenty members in all, perhaps a rota of four groups containing five people, responsible for preparing the acts of worship. They would be populated according to different gifting — e.g., a musician in each group, someone with scriptural knowledge or teaching ability in each group, and a mix of more and less mature Christians.

The sub-group with responsibility for worship would get everything needful ready; and also receive the participatory elements, sifting and ordering them appropriately.

In the 1980s, when I belonged to an inter-church group call the Ashburnham Stable Family, it was the responsibility of every person belonging to the meeting to listen carefully to the Spirit to discern what their participation would be in each passing week. Some choreographed a dance. Some composed a piece of music. Some believed they heard from the Lord in wisdom, or prophecy, or a direction to speak in tongues, or to announce healing. All these people would let those responsible for the meeting know, in advance, so their contribution could be integrated into an act of worship that flowed well and fitted the time frame.

Now, suppose one week you had five people who had all written a new hymn. That might be too much for one act of worship, so the sub-group on the rota would chose perhaps two of the proposed hymns — ones that well-fitted the theme or mood, or just the first two suggested — then pass the rest on to the next week's organisers for consideration.

And suppose you had Susan with yet another vision of a rainbow, you could include it because what's the harm? But suppose you had Tracey with a word from the Lord to buy sub-automatic weapons and mow down the children of the infidel, the organising group for the week would sift that out as inadmissible before it got to the meeting.

Thus the elements of the meeting would be structured into a flow, and participation would be both encouraged and monitored. The scriptural focus could be agreed by the whole group ("Let's study Romans/Micah over the next six weeks") or follow the circle of the church year. The organisers for the week would be responsible for seeing that all the agreed elements for an act of worship were included, either through participatory contribution, or by being put there by the organisers themselves. If the group as a whole had only one musician, or only one gifted teacher, then that person would be primed by the organisers, as well as listening to the Spirit him/herself.

Every so often — perhaps annually — the groups could be re-mixed to create teams with a different combination of skills and a different dynamic of personalities. This would decrease the likelihood of factions developing, and allow new combinations to allow new and sometimes surprising aspects of creativity and insight to emerge.

That's how I imagine it working.

One of us raised the question, what would happen about the Lord's Supper. Well, I think there's a lot to be said for having a familiar rhythm to at least some aspects of worship, so I think a few patterns could be worked out to become favourites. Not too wordy and heavy, because this would be an all-age group. Responsibility for preparation and for presidency would rest with whichever organising sub-group had their turn on the rota. It's not very difficult to celebrate the Lord's Supper without an institutionally accredited person; we have a good precedent after all, in the first time it ever happened.

One of us raised the question, what would happen about the Lord's Supper. Well, I think there's a lot to be said for having a familiar rhythm to at least some aspects of worship, so I think a few patterns could be worked out to become favourites. Not too wordy and heavy, because this would be an all-age group. Responsibility for preparation and for presidency would rest with whichever organising sub-group had their turn on the rota. It's not very difficult to celebrate the Lord's Supper without an institutionally accredited person; we have a good precedent after all, in the first time it ever happened.

Wednesday, 21 November 2018

Anarchist church leadership and protection

In the comment thread yesterday, Fiona said she'd like to read more thoughts about anarchist church, so here are some.

Several objections and questions to anarchist church could spring to our minds, so I thought it might help to look at some.

There might be a question about leadership. Who would lead an anarchist church?

Interestingly, Thomas Cranmer went to the stake over a similar question.

His examiner at trial was Thomas Martin.

Martin: Now sir, as touching the last part of your oration, you did deny that the Pope's Holiness was Supreme Head of the Church of Christ.

Cranmer: I did so.

Martin: Who say you then is Supreme Head?

Cranmer: Christ.

Martin: But whom hath Christ left here in earth His vicar and head of His church?

Cranmer: Nobody.

George Fox made a similar assertion the night following his ascent of Pendle Hill:

"Christ was come to teach people Himself, by His power and Spirit in their hearts, and to bring people off from all the world's ways and teachers, to His own free teaching, who had bought them, and was the Saviour of all them that believed in Him."

Thomas Jefferson said something very similar with reference to the political arena (but then leadership is the church is ecclesiastical politics):

"I know no safe depository of the ultimate powers of the society but the people themselves; and if we think them not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take of from them, but to inform their discretion by education. This is the true corrective of abuses of constitutional power."

Then one might ask — without accredited leaders, who will educate the people? I would say, life and experience will educate them, and discussion in the holy circle, and the exercise of compassion and self-discipline and holiness in their own lives, and prayer and the inspiration of the Holy Spirit.

We have never at any time in history been so well-placed to educate ourselves as we are at the present moment. The electronic revolution has placed within our grasp all the materials we need to supply us with information; what must be added to that is wisdom and discretion — do we not rely on accredited leadership for that?

You would think so, wouldn't you? But I have not found it so. Here and there I have seen admirable and beautiful shepherding of the flock by the leaders of the church denominations. But equally I have seen shameless abuse of power, and even more often weak and exhausted leaders held up by the kindness of their congregations when the requirements of leadership were beyond their capacity.

There might also be a related question about predatory people. Do we not need accreditation and appraisal to monitor leadership and protect us from abuses of it? Three decades ago I would have said, "Yes." Not today. I have had the opportunity over a lifetime of observing how the accredited leadership of the church works in respect of predatory, abusive, power-hungry, unstable individuals — and I would say now that in general it favours them. Such people operate by ignoring, manipulating and using the channels of power (which are respected by the good people of the flock of God) for their own advantage. And those best protected by accreditation, for good or bad, are not the people but the leaders themselves. Status accords a shelter.

In the worst situations I have experienced — I'm talking now about people who have lost their homes and jobs or committed suicide — I can trace a direct link to the abuse of power that was made possible by people in charge having the ability to bypass or override or simply not inform the people. My experience has been that if you consult, if you listen, if you take everyone with you, then you reach a far better result than if you impose power and control.

My most recent and immediate experience of this came on a Methodist Safeguarding training day, designed to acquaint those in leadership with the procedural and regulatory requirements of safeguarding vulnerable individuals again abuse.

At one point in the day we listened to a podcast describing a scenario where a youth leader had serially sexually abused children in his care (and been apprehended and imprisoned). The podcast told of three situations where he had worked — in two he had abused several children, in one he had not. In the two, all the correct regulatory and procedural safeguards were in place, yet he had still abused. In the one where he had not, he was left alone on duty, at night when the children were in bed, and yet he had not abused them. When asked why, he explained that he dared not touch these children because in this place the staff in general cared for and listened to and respected them. If he had crossed a line here, the children would have felt confident to tell the other adults, knowing they would be heard and believed.

But . . . surely . . . this doesn't inherently carry a recommendation for more procedures, more accreditation, for certification and status and power? It tells us to listen, to respect and pay attention to everyone even the smallest and youngest. It reminds us that the circle, not the pyramid, is the safest place to be. because in the circle, every pair of eyes sees. In the pyramid, the best (sometimes the only) view is from the top.

Several objections and questions to anarchist church could spring to our minds, so I thought it might help to look at some.

There might be a question about leadership. Who would lead an anarchist church?

Interestingly, Thomas Cranmer went to the stake over a similar question.

His examiner at trial was Thomas Martin.

Martin: Now sir, as touching the last part of your oration, you did deny that the Pope's Holiness was Supreme Head of the Church of Christ.

Cranmer: I did so.

Martin: Who say you then is Supreme Head?

Cranmer: Christ.

Martin: But whom hath Christ left here in earth His vicar and head of His church?

Cranmer: Nobody.

George Fox made a similar assertion the night following his ascent of Pendle Hill:

"Christ was come to teach people Himself, by His power and Spirit in their hearts, and to bring people off from all the world's ways and teachers, to His own free teaching, who had bought them, and was the Saviour of all them that believed in Him."

Thomas Jefferson said something very similar with reference to the political arena (but then leadership is the church is ecclesiastical politics):

"I know no safe depository of the ultimate powers of the society but the people themselves; and if we think them not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take of from them, but to inform their discretion by education. This is the true corrective of abuses of constitutional power."

Then one might ask — without accredited leaders, who will educate the people? I would say, life and experience will educate them, and discussion in the holy circle, and the exercise of compassion and self-discipline and holiness in their own lives, and prayer and the inspiration of the Holy Spirit.

We have never at any time in history been so well-placed to educate ourselves as we are at the present moment. The electronic revolution has placed within our grasp all the materials we need to supply us with information; what must be added to that is wisdom and discretion — do we not rely on accredited leadership for that?

You would think so, wouldn't you? But I have not found it so. Here and there I have seen admirable and beautiful shepherding of the flock by the leaders of the church denominations. But equally I have seen shameless abuse of power, and even more often weak and exhausted leaders held up by the kindness of their congregations when the requirements of leadership were beyond their capacity.

There might also be a related question about predatory people. Do we not need accreditation and appraisal to monitor leadership and protect us from abuses of it? Three decades ago I would have said, "Yes." Not today. I have had the opportunity over a lifetime of observing how the accredited leadership of the church works in respect of predatory, abusive, power-hungry, unstable individuals — and I would say now that in general it favours them. Such people operate by ignoring, manipulating and using the channels of power (which are respected by the good people of the flock of God) for their own advantage. And those best protected by accreditation, for good or bad, are not the people but the leaders themselves. Status accords a shelter.

In the worst situations I have experienced — I'm talking now about people who have lost their homes and jobs or committed suicide — I can trace a direct link to the abuse of power that was made possible by people in charge having the ability to bypass or override or simply not inform the people. My experience has been that if you consult, if you listen, if you take everyone with you, then you reach a far better result than if you impose power and control.

My most recent and immediate experience of this came on a Methodist Safeguarding training day, designed to acquaint those in leadership with the procedural and regulatory requirements of safeguarding vulnerable individuals again abuse.

At one point in the day we listened to a podcast describing a scenario where a youth leader had serially sexually abused children in his care (and been apprehended and imprisoned). The podcast told of three situations where he had worked — in two he had abused several children, in one he had not. In the two, all the correct regulatory and procedural safeguards were in place, yet he had still abused. In the one where he had not, he was left alone on duty, at night when the children were in bed, and yet he had not abused them. When asked why, he explained that he dared not touch these children because in this place the staff in general cared for and listened to and respected them. If he had crossed a line here, the children would have felt confident to tell the other adults, knowing they would be heard and believed.

But . . . surely . . . this doesn't inherently carry a recommendation for more procedures, more accreditation, for certification and status and power? It tells us to listen, to respect and pay attention to everyone even the smallest and youngest. It reminds us that the circle, not the pyramid, is the safest place to be. because in the circle, every pair of eyes sees. In the pyramid, the best (sometimes the only) view is from the top.

Tuesday, 20 November 2018

The anarchist church

In my politics, I come closest to the kind of anarchy Gandhi advocated — peaceful self-organisation. It is idealistic, and I feel it is probably biologically impossible to achieve; our animal nature seems to involve territorialism, acquisition and domination to an extent stronger than we can overcome on a broad scale, even when we're trying.

So I don't hold out hope that the human race will be unrecognisably transforming any time soon into one big kindly and generous family committed to sharing and lifting up the vulnerable. But hey, you never know, and when election time comes round I cast my vote towards the best fit; whatever I perceive at that juncture gives the most people the best chance most of the time.

But then today I was thinking about church, and how we organise it, and how well that serves us as a community. I've met some fine and loveable people in the church over the years, people I'm grateful to know and glad to walk alongside. Gentle, humble, forgiving, discreet, forbearing — wonderful, really.

These qualities are lovely to encounter and experience, but they can also tend to create a certain vulnerability to unscrupulousness. Over several decades I've had a number of opportunities to watch narcissists use confidentiality and discretion as a weapon to isolate and take down individuals who are in the way. I've watched people in power who are plainly out of their depth do a bad job at the expense of those delivered into their care. I've walked into a number of scenarios that made me think "Hmm . . .", a few where I had to stand my ground battered with insults and aggression, and one or two I simply had to leave.

And I now believe we have a small number of large things that make the church intrinsically different from my personal vision. These would be: paid clergy living in occupational housing; charitable status; hierarchical organisation; buildings; and the great big unwieldy clumsy thing our Safeguarding has become.

My vision of the church is not one of the punters in the pews who do as they're told, hand over their money and listen. Just the simple organisation of our buildings runs counter to what I am imagining. At the moment, most churches are organised into lines of seats facing a central podium where the speaker stands and the electronic screens are situated. The congregation can either look at the speaker or the back of someone's neck.

I'd like to toss out the podium and serried ranks, and rearrange the seats into a circle, so that what the people see as they gather for worship is each other's faces. Instead of an organ with its inherent fixity and dominance, I'd like the people who play instruments to bring them along and play from their places in the circle, keyboard included. I'd like all the worship to be all-age, and the children to be alongside their family members, so that all these police checks would become unnecessary. I'd like the ministry of the word to be participatory and responsive, working together to reach an understanding of how to keep faith with the scriptural truths of our salvation. I'd like space to allow expression for the now word of the Holy Spirit in the lives and hearts of the people. I'd like leadership to be locally formed and expressed. At present, our church is weakened by having leadership centralised, so that the church congregation is always pastored by strangers and the most visionary of its members are removed and sent away to work as strangers among strangers. I'd like our meetings to be housed in either public spaces such as village halls, or in our own homes. I'd like the way we organise ourselves to be so simple that it requires hardly any money at all.

In short, my vision is of an anarchist church.

I believe in peace, in respect, in listening deeply. I believe in the power for good of really knowing one another. Like George Fox, I believe that Christ has come to teach his people himself, and does not require an intermediary. I believe in openness, and in the power of the circle.

And I think, though the realisation of this is deeply unlikely, it could happen.

Sunday, 18 November 2018

Agnus Dei from Byrd 3-part Mass

Back in the 1970s when I was a student at York university, I was part of an interdenominational community — we called it the St Martin's Lane Community, because that's where we lived.

Father Fabian Cowper, Benedictine monk of Ampleforth Abbey, and the Catholic Chaplain for York University, was our chaplain. We shared daily prayer together, using the Ampleforth setting for Compline in the evening, and every Thursday we used to sing Vespers in Latin at All Saints Pavement Church.

As you know, it is important to me to keep my belongings to a minimum, but one of my absolutely treasured possessions (now owned only in electronic form), carried through the years, has been a recording three of our community members made of William Byrd's three-part Mass.

In the early 1990s, when I was writing my third novel The Long Fall, which traces the story of two men coming to terms with the profound illness and subsequent death of one of them, I listened over and over and over again to this Agnus Dei from the Byrd three-part Mass. It is one of the most beautiful pieces of music I have ever heard.

Roger Wilcock (whom I married and is the father of my children) sings the bass line; Michael Guilding sings the tenor line, and John Williams the counter tenor. Mike had an absolutely stinking cold the day they recorded the Mass, despite which he sang brilliantly — he loved that music dearly.

The picture accompanying the chant is of a stained glass panel by my daughter Alice Wilcock.

I do hope you like it. I am only just learning how to upload music to YouTube, but I have uploaded all the bits of that Mass for you to listen to.

Father Fabian Cowper, Benedictine monk of Ampleforth Abbey, and the Catholic Chaplain for York University, was our chaplain. We shared daily prayer together, using the Ampleforth setting for Compline in the evening, and every Thursday we used to sing Vespers in Latin at All Saints Pavement Church.

As you know, it is important to me to keep my belongings to a minimum, but one of my absolutely treasured possessions (now owned only in electronic form), carried through the years, has been a recording three of our community members made of William Byrd's three-part Mass.

In the early 1990s, when I was writing my third novel The Long Fall, which traces the story of two men coming to terms with the profound illness and subsequent death of one of them, I listened over and over and over again to this Agnus Dei from the Byrd three-part Mass. It is one of the most beautiful pieces of music I have ever heard.

Roger Wilcock (whom I married and is the father of my children) sings the bass line; Michael Guilding sings the tenor line, and John Williams the counter tenor. Mike had an absolutely stinking cold the day they recorded the Mass, despite which he sang brilliantly — he loved that music dearly.

The picture accompanying the chant is of a stained glass panel by my daughter Alice Wilcock.

I do hope you like it. I am only just learning how to upload music to YouTube, but I have uploaded all the bits of that Mass for you to listen to.

Friday, 16 November 2018

A quiet night and a perfect end

It’s early in the morning, the houses all wrapped round in the November mist. My husband has gone out to play golf with some combination of Mike, Andy and Ed, and I’m still sitting in bed writing — haven’t even brushed my hair or washed or cleaned my teeth. Though I’ve had a Frankincense pill and a cup of nettle tea.

I was thinking about prayers I knew from long ago.

The abbot gives the knock, the community rises, and Compline, the last office of the day, opens with the prayer:

May the Lord Almighty grant us a quiet night and a perfect end. Amen.

Then, when Compline ends, the day is over, the community enters the Great Silence, and they go their separate ways to rest.

It offers a metaphor of how a wise life aspires to end: quietly, prayerfully, recollectedly. And there was a beautiful Buddhist word I once loved, "mindfully", though I've gone off it a bit now it's been seized by word-peddlers and made into a Thing right up there alongside aromatherapy and colouring books. But that, anyway. With reverence, chanting, silence. That was how my husband Bernard's life ended. I had a CD of sacred chant, just one chant but forty-five minutes long, that he loved and I often played. Once they set up a syringe-driver with morphine to hold his pain, he descended into a sedated state, remaining there the last few days — longer than I thought it would be, about five days. On the last morning, as his breathing began to change, I put on the CD with the sacred chant, forty-five minutes, the family gathered quietly, and he took his last breath with the very last chord of the singing. We played it again as the people gathered for his funeral. Chant is very supportive to reverence, peace and wellbeing. I recommend it. I heard of a monastic community in France who, in obedient response to Pope John 23rd's encouragement to engage with modern life and get out and mix more, cut down their hours of chanting in chapel. But they were a bit radical in their trim, more of a savage prune really, and overdid it. They had to adjust back up when the men in the community began to get sick — under-chanted!

So I was thinking about Compline and that prayer, "May the Lord Almighty grant us a quiet night and a perfect end," and about how it touches upon an aspect of life it's easy to lose track of in the modern world.

If you read books on ageing, they (without exception in what I've read so far) focus on the contribution you can still make, the engagement you can still have, the things you can still do, the illnesses and ailments you can defeat. "Life in the old dog yet" kind of books.

And the old people I have known (not all, but many) have tended to take comfort in materialism and consumerism; while the light lasts, going shopping and having cruise holidays and coach trips and days out and buying things and involving themselves in deep layers of pastry — cream teas, afternoon tea, meeting friends in a café for morning coffee. "We've retired. Hooray! Let's go out for a meal and take in some shopping." Hips replaced, false teeth in, cataracts removed, orthotics in place, hearing aids switched on, we elderly go forth, eager to take refuge in the pleasures of the flesh that still remain, with a hunger for life and a delight in living that defies the lengthening shadows and the creeping cold.

The last office of the day is Compline, and the one before it, around tea-time, is Vespers, which is a cardinal office — called so from the Latin word cardo, meaning "hinge". The other Cardinal office is Lauds — so Lauds and Vespers are the hinges that open and close the day, then Compline takes you down into silence, a model of death. And the frantic whirl of shopping and holidays, the bumper stickers joking "We're spending the kids' inheritance", the taking refuge in pastry, is the creaking hinge of a Vesper as the day draws to its close — not yet the whispering chill and the advancing dusk, but the avid desire to soak up the sun's last golden rays.

This pattern of ageing belongs to consumer society, relying heavily on the support of money and manufacturing. There's nothing wrong with it — it exudes a joyousness and zest for living that I admire even though I do not share it. But it is quintessentially modern.

When I think back to the collects of the Book of Common Prayer, I trace the heart-patterns and preoccupations of a different age.

The prayer (Trinity 4) made to "God, the protector of all that trust in thee, without whom nothing is strong, nothing is holy," to "increase and multiply upon us thy mercy," that "thou being our ruler and our guide we may so pass through things temporal, that we finally lose not the things eternal.”

The prayer (Trinity 7) that God will “increase in us true religion, nourish us with all goodness, and of thy great mercy keep us in the same”.

The second collect from Evening Prayer, asking God to “give unto thy servants that peace which the world cannot give; that both our hearts may be set to obey thy commandments, and also that by thee we being defended from the fear of our enemies, may pass our time in rest and quietness”.

And so many others. Prayers from the days before antibiotics and germ theory, when death took so many so young, when any position of power or acquisition of wealth brought with it the fear of intrigue and violence — everything from politicians to footpads — and when those who stepped out of line were burned alive or decapitated or hung by the neck until dead. The collects of the Book of Common Prayer are redolent with sickness, violence and death as close presences, never far away.

Again and again, Cranmer begs his Lord for rest and quietness, for the necessary peace to lead a quiet life, and the recollection to keep our eyes resolutely on heaven and our hearts held safe in truth.

The Book of Common Prayer set for Evensong every day the lovely canticle of Simeon, the Nunc Dimittis:

Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace, according to thy word. For mine eyes have seen thy salvation . . .

This cardinal office to close the day is a different kind of hinge from the modern sort. Isn’t it?

When it comes to food, you will no doubt be acquainted with the hunger of under-nourishment. The sugar crash. The more . . . more . . . more . . . drive of refined carbohydrates. The food that makes you steadily hungrier the more you eat. And, conversely, the serenity that pervades the body once the liver is allowed to put down its toxic load and the lumen of the gut receives high quality nutrition. Real nourishment does give energy, but a quiet, steady kind, not the restless festination of the overstimulated.

I suppose, in my quest to find a way back Narnia, at the moment I’m groping through the encompassing darkness inside this wardrobe, pushing aside the enfolding furriness of so many stored coats to get to what lies beyond.

Chant, and quietness, and good nutrition, habits of recollection, silence, solitude and simplicity, will help me, I think.

May your day be blessed.

Thursday, 15 November 2018

Just because this is one of my favourite songs.

You can dance to that.

Appetites

When I was eighteen, I spent a while living and working with some monks in Devon.

There a Spanish priest who spoke no English taught me to milk a cow, and I learned to fill out a Post Office remittance sheet — fiendishly difficult; maths was never my strong suit.

Brother Jonathan was in charge of the enterprise, a big, heavy-built man with a luxuriant beard. He lived in an apartment above the Post Office, and the stone shed built into the back of it had been transformed into a small whitewashed chapel, furnished with low benches, sisal mats and sunshine. It opened into a little triangle of garden, where cabbages grew and my dwelling — a caravan — stood. Up the road in two cottages the various volunteers lived, and then a track led past the orchard (home to our goat) to the farm where the pigs, cows and donkey resided.

On the way to the farm, the track passed an old Methodist chapel. Brother Jonathan, not the easiest of men, had enjoyed a less than happy relationship with the local Methodists, so he said, and as the congregation dwindled the chapel steward had averred, through gritted teeth, "Over my dead body will that monk get his hands on our chapel."

You should be careful what you say about the servants of the Lord. He did die, and Jonathan did get the chapel, adding it to the straggle of buildings contributing to his vision of providing holidays for children from the inner city. In that particular building, nothing happened downstairs and we used the upper floor for amassing donations for our jumble sales, and for our stall. On Mondays we went to Bideford market to sell anything we could lay our hands on we thought might raise money.

My job was basically to do anything that needed doing — digging a vegetable clamp to store the root veggies through the winter, making pots of paté from a carrier-bag-full of chicken livers Jonathan had got hold of from somewhere, cooking supper for whoever was living there at the time, milking the cow, and helping in the Post Office and stores. That could be something of a nightmare. I well remember the day Jonathan left me in charge of the shop, when I discovered that not only had the mice nibbled all the bars of chocolate on sale, but when I opened the till to give the old people of the village their pensions it had nothing in it but I.O.U.s from Jonathan.

On Wednesdays I spent the afternoons filling out the remittance sheet with him, sitting by the Aga in his little sitting room behind the shop.

I remember him sashaying down the 1970s open ladder stairs to fill out the form with me, singing Hey Fattie Bum Bum and wanting to know why we never sang anything like that in church. A fair question.

And as we sat by the stove chatting, Jonathan remarked that he woke much earlier in the morning that he used to do as a young man. At the time I was all of eighteen and he was forty-three, but I listened with interest as he mused on the discovery that nowadays he needed less sleep but more rest. The thought intrigued me, and I tucked it away in my mental filing cabinet. There's all kinds of stuff in that.

And it's true for most people. As you get older, you need less sleep but more rest. You get tired, your reserves run low, you cannot be bothered, you have less stamina and less resilience. On the one hand. But on the other hand, you wake by four or five in the morning, and if something troubles you then you lie awake all night, just turning it over in your mind. Well, I do anyway.

I remember when I moved to York as a nineteen-year-old, getting up at 5am so I had time to walk through the city to join the Poor Clares for early Mass in Lawrence Street, it felt almost unbelievably heroic — I had to go back to bed the minute I got home. Five o'clock!! Ha! Nowadays I'm awake by five every day of the week.

More rest, and less sleep.

And just as your appetite for sleep diminishes, so does your appetite for food. Thirty years ago I used to look at the dinky plate of cake and sandwiches our old ladies nibbled on at chapel teas and wonder if they had a secret stash to fill up on at home. I used to get so hungry. I could polish off a big roast dinner followed by pie and ice-cream and come back for seconds. But gradually, as time has gone on, I find I want less and less. For breakfast I have some home-made carrot and apple juice and a bowl of oatmeal incorporating the fibre left from making the juice. For lunch I have a dessert plateful of something cooked, then a piece of fruit. For supper I have maybe a kale shake, or a small bowl of nuts, or some steamed greens. I'd have been ravenous if you'd fed me like that as a young woman, and lost weight like water running out of a sink when you pull the plug. My spare tyre still sits comfortably round my waist these days, though. And if I try to eat any more — like if we go out to eat at a restaurant, for example — it just makes me feel spectacularly ill.

This even applies to cups of tea. The amount of liquid in one of the big mugs from which I used to drink tea, I'd find overwhelming now. A small mug or a teacup is better. And then of course, there's the tea itself; it has to be herb tea now — I can no longer cope with regular tea, not even Earl Grey.

Less sleep, then, and less food.

And what about sex?

Heheh. My previous marriage, short and sweet, was to Bernard. He and I got together when he was seventy-one, and he died when he was seventy-three. We had a very full and happy sexual relationship — but it was not the same as for younger people. I would say my general experience of sex in older people is that it is, in general, sweeter and more pleasurable than sex in younger life, perhaps in part because its rhythms are slower and more mellow. It is not without intensity, but physical energy does not always keep up with sexual desire, and one has to make corresponding adjustments.

Other than that, I find my appetite for excitement is now sub-zero — I can no longer watch tense stories laden with threat on the telly; I even find driving a car quite difficult! But I never tire of the ordinary; I like my spotted hanky, the smell of woodsmoke, sunlight slanting through trees silhouetting against the wall, someone playing the harp downstairs in the evening . . . But outings are almost a thing of the past. I very occasionally go to the cinema, but I think I'd find a full-on day in London with a restaurant meal, and then on to the theatre for Shakespeare or the ballet, all a bit more than I could cope with now. A 40-minute lunchtime concert in a local venue is more like my mark.

I don't miss these things, though. I like lying awake in the early morning and pottering about while the household is asleep. I'm happy with less to eat, and I don't miss days out or holidays. I think the only thing I have given up that causes me sadness is Earl Grey tea and cake. Yes, I do miss those.

There a Spanish priest who spoke no English taught me to milk a cow, and I learned to fill out a Post Office remittance sheet — fiendishly difficult; maths was never my strong suit.

Brother Jonathan was in charge of the enterprise, a big, heavy-built man with a luxuriant beard. He lived in an apartment above the Post Office, and the stone shed built into the back of it had been transformed into a small whitewashed chapel, furnished with low benches, sisal mats and sunshine. It opened into a little triangle of garden, where cabbages grew and my dwelling — a caravan — stood. Up the road in two cottages the various volunteers lived, and then a track led past the orchard (home to our goat) to the farm where the pigs, cows and donkey resided.

On the way to the farm, the track passed an old Methodist chapel. Brother Jonathan, not the easiest of men, had enjoyed a less than happy relationship with the local Methodists, so he said, and as the congregation dwindled the chapel steward had averred, through gritted teeth, "Over my dead body will that monk get his hands on our chapel."

You should be careful what you say about the servants of the Lord. He did die, and Jonathan did get the chapel, adding it to the straggle of buildings contributing to his vision of providing holidays for children from the inner city. In that particular building, nothing happened downstairs and we used the upper floor for amassing donations for our jumble sales, and for our stall. On Mondays we went to Bideford market to sell anything we could lay our hands on we thought might raise money.